"Buttons"

- An extra lie, not included in A Book of Untruths -

I Can Sew

It is not clear whether the Countess R is assessing my potential when she asks me to sew a button on her son’s dress shirt. Or whether she is asserting an above and below stairs divide. But let us presume, because she puts me in the back kitchen, that her motivation is the latter.

I have been invited to join a Scottish Country Dance party in Inverness and must wear a doctored bridesmaid’s dress to the ball. A seventeen year old, Lord D, is joining the party and will drive.

The Earl & Countess R live on the enormous estate and castle at the top of the hill, and we live on a terrace at the bottom. To my mother this invitation is the plot of Cinderella and her excitement drives her to wash the car.

The Earl of R has been forced into a wing of his turreted pile on the Firth of Forth by a paying public, and when I get out of the car it is not clear where the owners are to be found. The clean car, and my mother’s best frock are ignored by the underling who eventually appears at a side door. I am taken up a dark back stairs to the flat in which the family continues to cling.

Lord D is still in his bed. My mother has delivered me too early. Breakfast is on the go, and rather than invite me to join them, the Countess R asks me if I sew. Like a storybook Princess the answer should have been a defiant ‘No’ But my mother has brought me up for deference and a respect for one’s betters, so I say humbly that I do.

The Countess puts me in Mrs Morrison’s back kitchen, and goes off to look for the shirt. I wait with the sewing box.

She is a slender woman, and to my adolescent eye not very countess-ish. Merely tweedy, unhappy and old.

When she returns with the garment, she briefly points to what must be done. I am left alone to struggle with the button. No Rumplestiltskin comes. It is a beautiful dress shirt in the finest Egyptian cotton. Everything but the laundered front pique is covered with cheerful primary coloured squares.

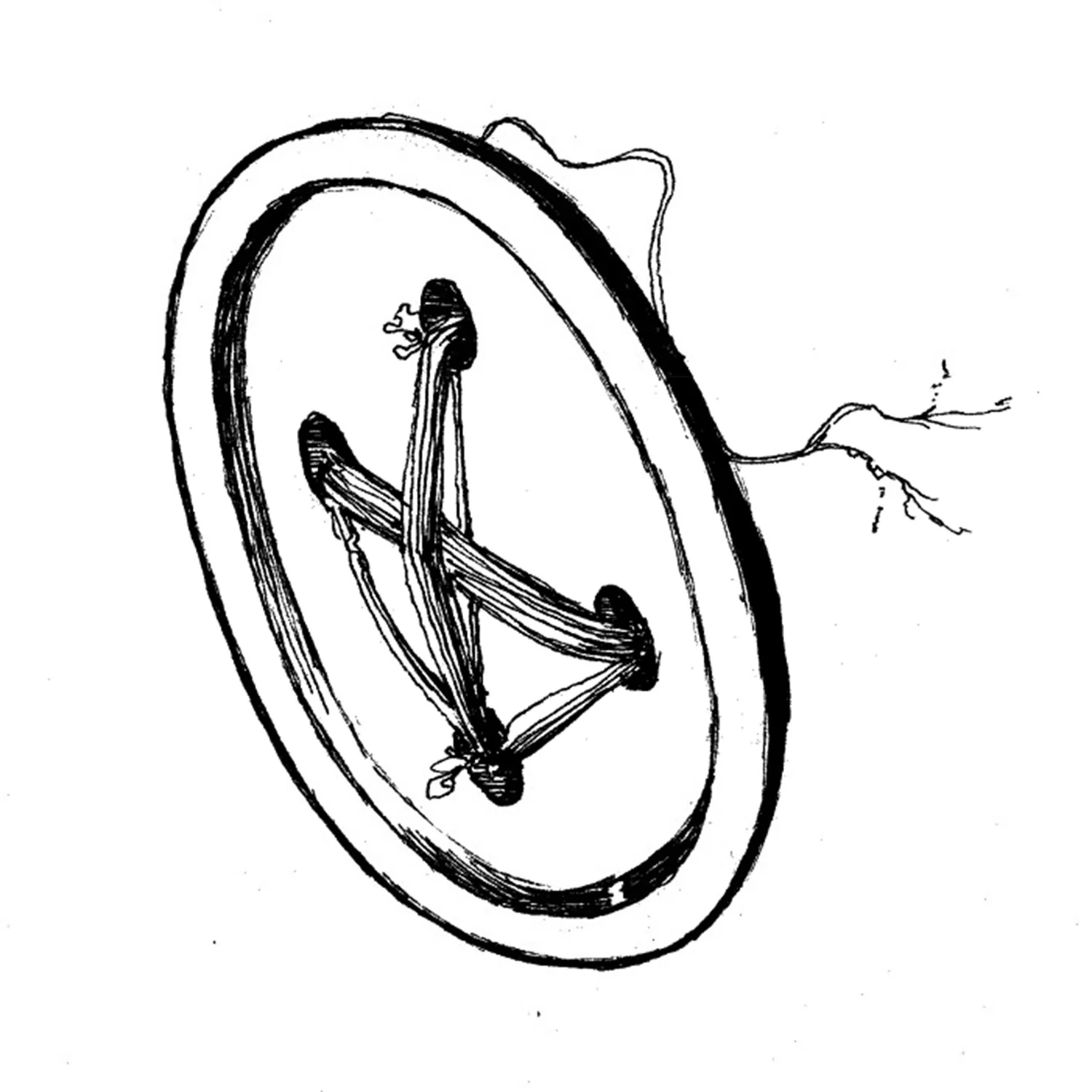

My mother learned sewing skills at a finishing school in Switzerland, and was able to knot her thread with a flourish I’ve never been able to learn. I struggle that morning with holding the button in its place, with threading the needle, with aiming it up through the holes, and consequently form no cross of thread between them, but a random filling up of fibre till the button is all but overwhelmed.

Finished, I wait again. The clatter of breakfast waxes through the apartment, but the place is like a warren, and I am not ill-mannered enough to feel I can drift between rooms. It is ages that I sit with the shirt and the sewing box in Mrs Morrison’s windowless room. Eventually the Countess returns.

She examines the shirt with scorn. Of course I have butchered it with a scruffy knot of nylon. I have not made the impression my mother would have liked.

There are still breakfast noises breaking along the corridor. Or is it elevenses, one meal bleeding indolently into another and Lord D still not out of his bed. The Countess looks around the room. Perhaps she does not know what to do with me.

‘I suppose you would like to join us,’ she says.

We move along the corridor, where dark furniture crowds sentinel along the walls. The breakfast room is congested with nearly three centuries worth of inheritance. It is as though the ground floor has been flooded, and everything hauled up stairs, out of danger’s reach. There is a sideboard and glass fronted cabinets; an enormous mahogany table fills the room, one of the vacant chairs forced to jut over the threshold of the open door.

Ornate light fittings in filigree cast a yellowy gloom. A cross hatched view of the lawn and tree, through diamond panes of glass, is watched by a maiden aunt. The Earl is over by the window, a Telegraph spread out in front of him, a riding crop beneath one palm.

The maiden aunt acknowledges me with a brief smile. The Earl does not. I am shown the seat nearest the door, the one that is neither in the breakfast room nor out, and offered a cup. The Countess and her sister resume their conversation. I worry over my manners, with the cup, and the saucer, the noise of my spoon.

I think the lie has been the one about sewing and my not being able to. But the deceit loiters there in the room, though these two women would talk it away with inconsequence if they could.

I cannot remember what precipitates the Earl’s sudden violence. His wife’s words? The Maiden Aunt’s? The newspaper which crowds black and white in front of him? But soon he is beating the table with the riding crop. He thrashes it. The cups and spoons and dirty plates shudder and clatter and bounce. The maiden aunt’s shoulders twitch like she would like to scrunch them up around her ears. But the Countess is inviolable. No flinch. No blink. She continues to speak, the only evidence of the beating in her raised voice. She is the older woman of every fairy tale, straining to keep the story together and her conviction is daunting.

When the belting of the table is over, the maiden aunt dabs the corner of her mouth with a napkin. The filigree encased lamp shades sway on their chain, light tossing across the walls like we are at sea.

The Countess will not look at me. The back kitchen I see was not to keep me in my place, but to protect hers, a place as fragile as the balance of the overhead light which is only now beginning to still.